Reproduction of ten information boards which have been produced for the Heinrich Barth House in Timbuktu with the support of the German Foreign Office

HEINRICH BARTH

A name as a scientific and cross-cultural programme

Heinrich Barth (1821-1865) is probably not the best known in this country, but scientifically the most important Africa researcher of the 19th century. Historical research, geography, linguistics and ethnology in Africa worldwide are based on his work, the aim of which he himself once described as the "historical connection of man with the rich organisation of the earth's surface".

Born in Hamburg on 16 February 1821, he studied philology, geography and history in Berlin and received his doctorate in 1844 with a dissertation on the trade relations of ancient Corinth. He was particularly interested in the Mediterranean basin as a habitat and source of diverse cultural and historical developments, which he pursued on his first journey through Spain, the Maghreb countries, Libya, Egypt, Nubia, Palestine, Asia Minor and Greece from 1845 to 1847. However, his real life's work, which earned him a worldwide reputation as an African explorer, was founded on his "great journey" through the Sahara and Sudan, which he undertook from 1850 to 1855 on behalf of the British government. His findings were published as early as 1857 in a five-volume, richly illustrated work in both German and English.

Despite his internationally recognised academic achievements, he was denied a chair for a long time, not least because - contrary to the thinking of his time - he recognised Africa's "historicity". His work, which emphasises the intrinsic value of African culture against the background of his own deep roots in the western-antique world without any colonial conceit, builds bridges between the continents and is held in high esteem as an authentic testimony to pre-colonial culture and history, especially in West Africa. At the same time, his interdisciplinary scientific view of the connections between humans and the environment also points the way forward for today's interdisciplinary research in Africa.

"Kein Forscher hat soviel wie Barth dafür geleistet, von Afrika ein gleichzeitig wissenschaftlich fundiertes und von Sympathie getragenes Bild zu vermitteln."

(Joseph Ki-Zerbo )

"Mit seinen detaillierten Schilderungen ... schloß er uns einen wichtigen Weltteil auf, der in der zusammenwachsenden Welt heute zu einem nahen Nachbarn geworden ist."

(Richard von Weizsäcker )

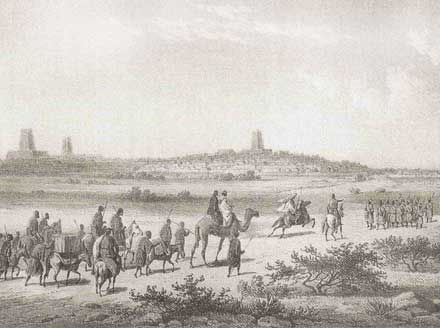

Heinrich Barth's Great Expedition through the Sahara and the Sahel

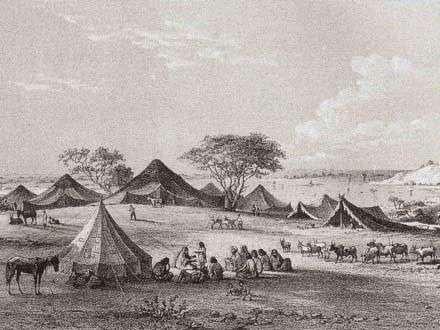

In 1849 Barth joined a British expedition to Lake Chad aiming to establish closer contacts with the Empire of Bornu, put a stop to the slave trade through the Sahara and carry out scientific studies. His five-year journey covering almost 20,000 km took him to the land of the Tuareg, to Bornu, North Cameroon and finally to the ancient caravan metropolis of Timbuktu. Barth's three companions all died during the journey and in Germany Barth himself was for a long time believed dead.

Heinrich Barth's 3,500 page-long magnum opus "Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa in the Years 1849-55" constitutes the greatest individual achievement in nineteenth- century African studies. His report deals at length with different ethnic groups and regions, providing a wealth of information on languages, customs, political institutions and Islam in Africa. Right to the present day scholars in this field consider it an invaluable source on the history of North and West Africa.

"Ich bin niemals weiter vorgedrungen, ohne zu wissen, dass ich hinter mir einen aufrichtigen Freund liess." (Barth 1857, I: XIII)

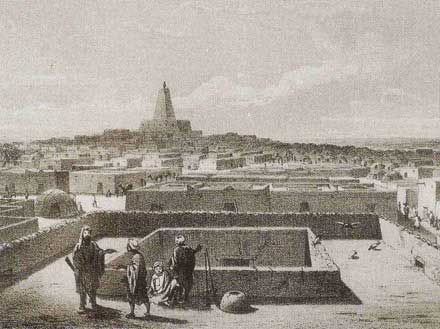

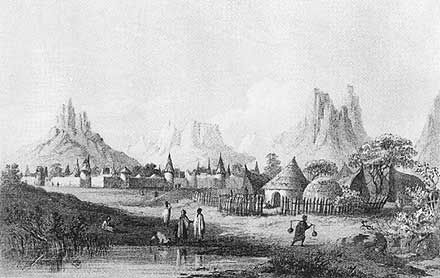

Heinrich Barth in Timbuktu

Heinrich Barth spent six months in Timbuktu and the surrounding area, collecting information on the life, customs, history and language of the Tuareg. He was accorded the personal protection of Sheikh al-Baqqai, with whom he developed a close friendship. The Moslem enjoyed conversing with the Christian traveller and allowed him access to valuable manuscripts, notably chronicles of the history of the Sudan, which reinforced Barth's conviction that the African continent had indeed a history of its own. AI-Baqqai put at Barth's disposal the house which today serves as a memorial to the great African explorer.

"[Timbuktu war] der berühmte Sitz mohammedanischer Gelehrsamkeit, der Mittelpunkt religiösen Lebens; keine Stadt des Reichs besaß so stattliche Moscheen, keine überhaupt so schöne und massive Gebäude. [... ] Wie groß aber der Einfluß war, den Timbuktu als Sitz der Intelligenz beanspruchte, geht schon daraus hervor, daß der Tumbo-koy oder Statthalter, wie es scheint, stets ein 'Faki', d.h. ein gelehrter Mann, sein mußte." (Barth 1860, II:281)

Heinrich Barth and African Cultures

Heinrich Barth was willing to accept other cultures and ways of life, even though from his European vantagepoint he might also suggest improvements. He was no dispassionate observer and expressed his horror at the cruelty inflicted by man upon man, in slave raids, for instance. Above all, however, he viewed European influence in Africa with considerable scepticism and even dreamed of leading a pan-African army to drive the European colonial powers out of Africa. No other African scholar of the time placed himself so unreservedly on the side of the Africans.

In the course of his five-year-long journey he won many friends, without whose spiritual and material support his undertaking would not have been possible. Still today African scholars rate Barth and his achievements very highly.

"Wer unter Völkerschaften des verschiedensten Charakters und der verschiedensten Glaubensformen gelebt hat und bei allen in ihrer Weise treffliche Menschen gefunden hat, der wird sich vor der Einseitigkeit der Anschauung menschlicher Lebensverhältnisse bewahren." (Barth 1859)

Heinrich Barth and Geography

Heinrich Barth's journey took place at a time when European geographers were preoccupied with the quest for the sources of the Nile and the question of the existence of a great lakes area in Africa or snow-covered mountains below the Equator. Barth, however, was interested primarily in finding out how a landscape shaped its inhabitants and their way of life, a concern still at the heart of cultural-ecological research today. Barth's focus then was on geomorphology, the study ofclimate and hydrography as well as patterns of human settlement and economic and transport geography. Many of the regions he travelled through were unknown to contemporary European scholars and it was only with the help of his detailed maps and itineraries that great white expanses on the Petermann maps of Africa could be filled in and the topography described. It was Barth's achievement to have written the first scientific account of large parts of what is now the Republic of the Niger, Nigeria, Southern Chad and North Cameroon.

"Der Leser wird, auch ohne daß ich es hier ausspreche, bald meine Art der Anschauung wahrnehmen. Es ist der historische Zusammenhang des Menschen mit der reichen Gliederung der Erdoberfläche." (Barth 1857, I: XVII)

Heinrich Barth and Cultural Anthropology

Heinrich Barth's great travel opus provides a fund of ethnographical material on North and West Africa. Barth was interested in patterns of human settlement, the influence and status of political institutions, commercial and economic structures, crafts and dress, food and medicine as well as the history of the areas he visited. His precise sketches give us a detailed picture of the material culture of North and West Africa in the middle of the nineteenth century.

With the help of Arabic sources and oral tradition, he recorded genealogies of African dynasties. Unlike most African travellers in his day who tended to spread fantastic tales, Barth with his sober style and critical approach to his sources heralded a new era of anthropological studies.

"Was ist belehrender für die Jugend als die Erd- und Völkerkunde in allen ihren belebenden und beseligenden Charakterzügen? Für mich selbst in der Tat ist diese Wissenschaft der Inbegriff, das einigende Band aller übrigen Disziplinen, und gerade wie die verschiedenen Zweige der Wissenschaft sich ihrer im Leben haftenden Wurzel immer mehr bewußt werden, muß diese Wissenschaft stets größere Bedeutung gewinnen." (Barth 1865)

Heinrich Barth and Archaeology

Heinrich Barth's deep interest in archaeology was already in evidence during his Mediterranean travels: He was therefore fascinated by the traces of ancient civilizations he came across in the Sahara, which he attempted to interpret in the light of his knowledge of classical times, notably the rock engravings he described and copied in 1850 in the northern Sahara. At a time when the study of prehistoric and early history was still in its infancy, he was one of the first to recognize that the rock engravings were extremely ancient, a significant historical source and testimony to the early inhabitants of the Sahara and their culture. He also regarded the engravings as evidence of the dramatic changes which had taken place in the climate of the Sahara over the past millennia.

"Kaum hatten wir hier unser Zelt aufgeschlagen, als wir fanden, dass das Thal einige bemerkenswerte Skulpturen [Gravierungen] enthielt, wlche unserer besondern Aufmerksamkeit werht waren." (Barth 1857: I: 210)

Heinrich Barth and History

By his own account Barth's prime interest was the history of Africa and he was a great pioneer in this field. In contrast to the conventional wisdom of his time Barth believed that Africa did indeed have a history and that a deeper understanding of world history was impossible without reference to the history of Africa. The methods he employed to study the continent's past were many and varied, ranging from comparative linguistics, the study of Arabic manuscripts and oral traditions to the interpretation of rock art.

His revolutionary approach made Barth one of the nineteenth century's most outstanding historians but at the same time brought him into conflict with many of his European colleagues. Although not always aware of their eminent predecessor, contemporary scholars of African history are still working with the methods he pioneered.

"Denn auch die Völkerbewegungen Central-Afrika's haben ihre Geschichte, und nur indem sie in das Gesammtgebilde der Geschichte der Menschheit eintreten, kann das letztere sich dem Abschluss nähern." (Barth1857, II: 82)

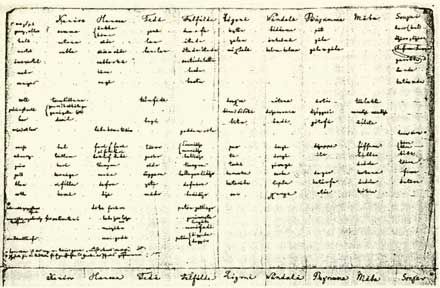

Heinrich Barth and Linguistics

With his background in linguistics, Heinrich Barth was well versed in the methods of historical linguistic research and applied them to the study of the African languages he came across on his travels. Besides English, French and Arabic Barth spoke several dialects of the Tuareg language as well as Kanuri, the official language of the Bornu Empire, Hausa, the chief lingua franca of West Africa, and also Songhai and Fulani, the language of the Fulbe. He also compiled extensive vocabularies of nine West African languages, which enabled him to trace linguistic relationships and historical links between different peoples. In the mid-nineteenth century these methods were revolutionary, so that Barth can rightly be said to be the founder of the scientific study of African languages.

"Jeder der fremde Länder besucht hat, weiß, wie unendlich leichter man sich da deren Sprache aneignet, als im langweiligen Studium ohne Anhalt daheim." (Barth 1862)

Heinrich Barth and the Islam

Most unusually for the time, Heinrich Barth had a marked sympathy for Islam, which he recognized as one of the world's great religions. While still at school he learnt Arabic and the first journey he undertook after completing his university studies was to the Islamic countries of the Mediterranean. Under the pseudonym of Abd al-Karim (Servant of the Most High) he travelled Africa, collecting a wealth of information on the history of Islam, a powerful influence throughout the Sahel region. In particular Barth sought out and enjoyed conversing with local Islamic scholars, and some of the character sketches of these figures are among the most vivid accounts of non-European cultures left us by any European travellers. Between Barth and his Timbuktu host, Sheikh al-Baqqai, the leading Koran scholar of West Africa, there developed an intellectual friendship. At a time of fanatical anti-Islamic fervour in Europe Heinrich Barth was the only African traveller of his day to oppose the missionary activities of the Christian churches in Africa.

"Ich wies ferner darauf hin, wie wir bei dem Glauben an einen und denselben Gott trotz der Verschiedenheit unserer Propheten und einiger geringen Abweichungen in unseren Sitten denselben religiösen Grundsätzen folgten, so daß wir einander näher standen, als er [Auab] glaubte, und wohl gute Freunde sein könnten." (Barth 1860, II: 307)

Brochure accompanying this project:

Reprint of Heinrich Barth's travel diaries: