- Herausgeber/in:

- Editor:

- Frank Förster & Heiko Riemer

- Erscheinungsjahr:

- Publication year:

- 2013

- Reihe & Band:

- Series & Number:

- Africa Praehistorica 27

- DOI:

- DOI:

- 10.18716/hbi/ap27

- Preis:

- Price:

- 78 €

- 78 €

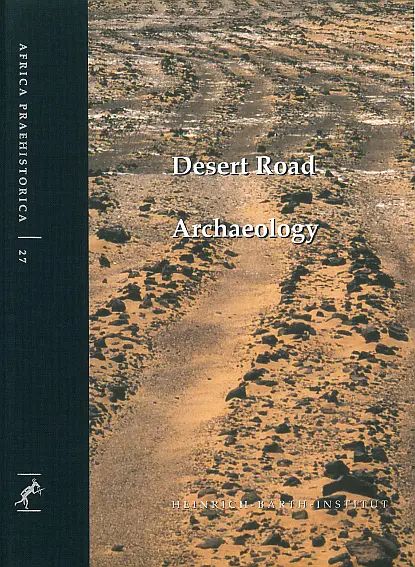

Nach ägyptischen Maßstäben gab es westlich der Oasen kein Wasser, und die Welt endete. Diese Aussage von Ralph Bagnold im Geographical Journal von 1937 richtete sich offenbar sowohl an die alten als auch an die modernen Ägypter, und sie spiegelt die Haltung der meisten Ausländer angesichts der ägyptischen Annäherungen an die Wüste genau wider. Wenn das "Ende der Welt" bedeutet, dass es "keinen Weg über diesen Punkt hinaus gibt", so wird diese Ansicht nun durch den vorliegenden Band in gewisser Weise widerlegt. Er stellt zum ersten Mal ein Netz antiker Routen zusammen, die das "Nirgendwo" der Wüsten in und um Ägypten erschließen. Diese Routen stimmen jedoch kaum mit allen existierenden modernen Karten überein, einschließlich der neueren Ausgaben von Michelin und Bartholomew, die insbesondere für die Libysche Wüste weitgehend nicht existierende Fantasiestraßen zeigen, abgesehen von den wenigen asphaltierten Autobahnen. So kann man sich leicht vorstellen, wie die ursprünglich breiten Verkehrswege nach und nach auf Pfade reduziert wurden, die von Ochsen, den wahrscheinlichsten frühen Lasttieren, angelegt wurden. Um etwa 3000 v. Chr. wurden die Ochsen durch Esel ersetzt, die besser geeignet waren, die wachsenden Entfernungen zwischen den noch bewohnbaren Orten zu überwinden. Als im letzten Jahrtausend v. Chr. das Kamel den Esel ablöste, mussten sich die Routen aufgrund der natürlichen Bedürfnisse des Tieres teilweise ändern, aber sie verbanden weiterhin das Niltal mit den weit entfernten Inseln im Ozean der Trockenheit und den dahinter liegenden Küsten.

By Egyptian standards there was no water west of the oases, and the world ended. This statement by Ralph Bagnold in the Geographical Journal of 1937 was apparently aimed at the ancient as well as at the modern Egyptians, and it accurately reflects the attitude of most foreigners in the face of Egyptian approaches to the desert. If the "world' s end" means "no way beyond this point", this view is now disproved to some extent by the present volume. It compiles, for the first time, a network of ancient routes that open up the 'nowhere' of the deserts in and around Egypt. These routes however show little concordance with all existing modern maps, including recent editions of Michelin' s and Bartholomew's, which, in particular for the Libyan Desert, widely present non-existing fantasy roads, except for the few tarmac highways. Accordingly, it is easy to imagine how the initially broad lines of communication were successively reduced to trails created by oxen, which were the most probable early beasts of burden. By about 3000 BC, these oxen were replaced by donkeys, which were better adapted to master the growing distances between the places that still remained inhabitable. When the camel took over from the donkey during the last millennium BC, the routes partly had to change due to the natural requirements of the animal, but they continued to connect the Nile Valley to far distant islands in the ocean of dryness and the shores beyond.